Cyber Crime in the Broadcast and Entertainment Industries

Security in content management has leapt to the top of the broadcast and entertainment industries’ agenda in the wake of the WannaCry ransomware attack earlier this month.

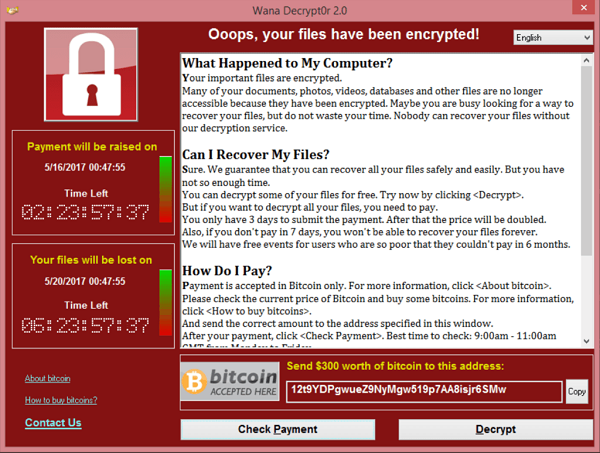

The use of ransomware – a cyber attack that involves hackers taking control of a computer system and blocking access to it until a ransom is paid – spiked from 2015 to 2016, and has become the fifth most common type of malware.

WannaCry was an indiscriminate, global cyberattack which targeted computers running Microsoft’s Windows operating system (despite Windows XP grabbing headlines due to its use in the NHS and other institutions, Windows 7 was the worst-affected operating system).

It was spread via the internet and local networks, encrypting data and demanding Bitcoin ransom payments.

The WannaCry attack hit many thousands of computers in 150 countries, including the UK, where the NHS was severely impacted.

It has brought the issue into the mainstream, and it’s not just national institutions who are at risk.

Any organisation – large or small – with a centralised data storage or computer resource, such as network-attached storage (NAS). And the risk applies even if your computers’ security software is up to date.

“Small businesses suffer because they don’t have the skill nor the infrastructure to manage this,” said Robert Gibbons, the chief technology officer at Datto, a cybersecurity company.

But what of the broadcast and entertainment industries?

As Jon Morgan, chief executive of Object Matrix, a Cardiff-based data storage company, wrote on broadcastnow.co.uk:

Disney reportedly suffered the ‘theft’ of the latest Pirates of the Caribbean movie, Dead Men Tell No Tales, also this month, when a digital copy was taken from an LA post-production company.

The hackers, according to The Guardian, “demanded a ransom, believed to be $80,000 (£61,700) – peanuts for a franchise that has pulled in $3 billion globally.”

But Disney have refused to pay and is working with federal investigators.

What’s more, there is strong argument that the perpetrator(s) in this case targeted the wrong content.

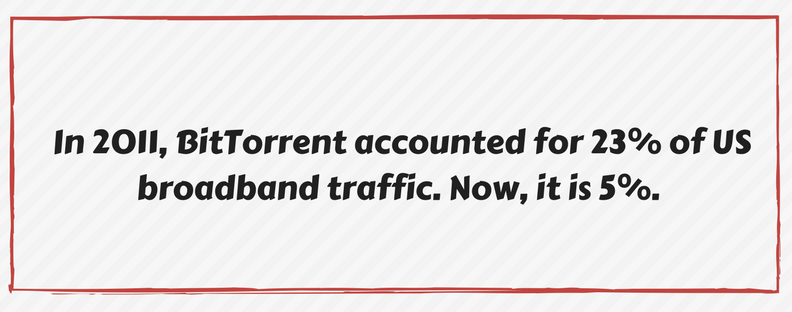

Audiences have moved on. While one particular demographic – men between the ages of 15 and 25 – continue to download through torrent sites, the rest appear quite happy with the big OTT services, who provide hassle-free, well-priced content…which is why a Pirates of the Caribbean film appears an odd one to target.

The ransom demand of Disney came only weeks after a hacker uploaded 10 episodes of the new season of Orange Is the New Black to The Pirate Bay after Netflix refused to pay an undisclosed amount. The episodes were posted on Pirate Bay six weeks ahead of the series’ official launch on June 9th.

The hacking group’s motives were more likely to do with Sony suffering than making money, since the information that was leaked would have been more valuable had the criminals kept it secret for extortion purposes.

Also in Hollywood in 2017, several media agencies have been targeted.

How does it work?

An ‘encrypt or destroy’ app can run quickly because…

Cybercrime – who’s responsible?

Various groups or individuals motivated by personal reasons:

- An (ex-)employee through physical access to servers possibly to take revenge

- Anti-security/hacking groups such as Anonymous, the international network of anarchic activist and ‘hacktivist’ entities through remote hacking, possibly for nothing more than personal enjoyment or, perhaps, more political reasons such as targeting companies who work to counter digital file-sharing

- Cyber-criminals, who account for most malicious internet activity

A ‘kill switch’ and a new tool offer hope...

A self-trained 22-year-old security expert from south-west England halted the spread of WannaCry by activating its kill switch.

Marcus Hutchins registered a web address acts as a beacon for the malware, which if contactable tells WannaCry to cease and desist.

Also, a new tool capable of restoring computers infected by WannaCry ransomware has been created by a security researcher.

It won’t work for all those affected but Adrien Guinet’s potential solution, WannaKey, which is designed to take advantage of a shortcoming in Windows XP to decrypt an infected machine’s files, could help.

“In order to work, your computer must not have been rebooted after being infected,” says Mr Guinet, who adds that an element of luck is required for his software to work.

WannaCry is demanding a payment of $300-$600 from victims.

In The Frame - April '23

In The Frame - March '23